Gaze into the Abyss

Or why, if you gaze into the abyss, some answers might gaze back

The Next Founder helps founders build great startups. We offer advice on managing your mental health and productivity, hiring and managing great people, building a strong culture, and keeping people aligned and working on the right things. See the series overview at Welcome to The Next Founder and find out more about me at My Story.

In “Gaze Into the Abyss,” we’ll discuss what founders can do to manage imposter syndrome, which, although common among startup founders, can hurt their startup and make them miserable.

“If you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

“Keep your shadows in front of you—they can only take you down from behind.”

— Carl Jung

“Running a start-up is like chewing glass and staring into the abyss. After a while, you stop staring, but the glass chewing never ends.”

— Elon Musk

Wow, nice abyss

You take your boyfriend to a local jazz club on Friday night. He asks how your week was, which he soon regrets after you spend twenty minutes talking over the music, unloading your litany of woes on him.

You launched your product six months ago. You have a handful of occasional users, but their feedback is lukewarm, and your meager revenue barely pays the kombucha bill. You aren’t converging on product/market fit, and you’ve been slow to launch experiments since your three engineers bicker constantly. Microsoft is also rumored to be adding some features to Azure that would compete directly against you and smother your market while it’s still in the crib.

Your boyfriend’s pupils expand as you toss rhetorical questions at him. Should we pivot and attack the market from a different angle, or be patient and stay the course? Should we fire the engineers and rebuild the team, or do we endure the dysfunction since we can’t stall the work at a pivotal moment? Will Microsoft lose interest like big companies often do, or are we wasting time thinking we can compete against them?

Your boyfriend is still paying attention, but it seems effortful. He wants to help, but since he works as a pastry chef, he has limited insight into your nascent niche in the AI tools landscape. But he makes an excellent sounding board, so you feel free to ask the real question: was this startup a mistake? Are my co-founder and I deluded in thinking we can do this? Should we just quit? At least date night would be more fun.

The good news is that if your boyfriend is willing to stay on board this carnival ride, he’s a keeper. The other good news is that you are willing to Gaze into the Abyss.1

It can get abyssmal

Successful startup founders write a business plan, raise money, hire a team, build the product, sign up customers, scale the company, and then sit back and sift through the potential exit opportunities that land in their inboxes.

LOL, just kidding, that never happens.

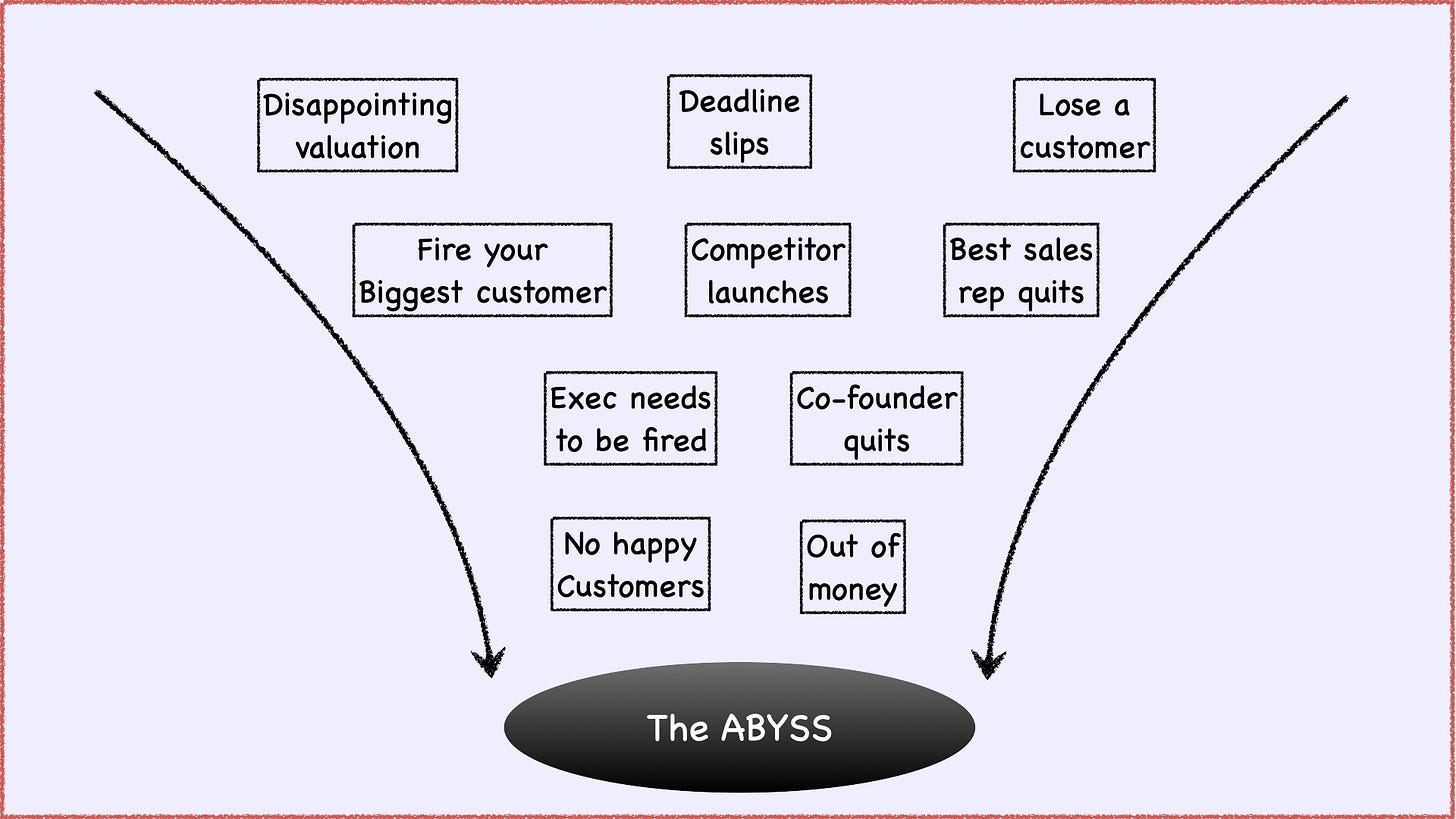

Every startup, even a successful one, constantly fends off an onslaught of problems, like a spaceship in a sci-fi movie dodging lasers, ricocheting off of asteroids, and careening toward black holes that threaten to suck them into oblivion.

Some problems, like a bad hire or a lost deal, are recoverable if you move quickly. Others, like trying to win a market that doesn’t exist, are existential threats. Some situations are so bleak that you are better off shutting the company down, taking a break, and starting a new startup from scratch.

These are “abyss” moments. An abyss isn’t just one of startup life’s long series of day-in/day-out challenges. They are company-defining moments where a brutal truth emerges. An abyss is realizing everything you asked your team and investors to believe was false. Escaping an abyss requires a bet-the-company decision with no clear answer.

Typical startup abysses are when you realize that:

You are not converging on product/market fit. You are solving a problem no one cares about, or you are solving it for the wrong customers. Or maybe you just built a lousy product. You need to rewind and rethink your product, possibly starting from scratch with a new problem to solve or a new market to tackle.

You hired several weak team members, and no amount of time, training, or leadership will turn them from the wrong people into the right ones. You have to ask them to leave and devote months to hiring and training replacements.

You will miss your revenue plan by a mile even if you close every deal in your pipeline. You’ll run out of money faster than expected, so you need to raise money quickly or lay off some of your team.

You raised money at a crazy high multiple during the last bubble and are facing a crushing down round. You tried to convince yourself that you’ve “grown into your multiple,” but the more likely case is that you’ll struggle to raise a round at any price.

How can you tell when a problem is an abyss? A few symptoms are:

You are tempted to deny it

Almost everyone is slow to accept harsh truths or even deny them, especially truths that put the viability of your company into question and thus your competence as a founder. For example, accepting that you hired the wrong VP of Sales would require admitting you made a bad hire, losing all of the time and money you spent recruiting and training them, and living without a VP of Sales for the year it will take you to hire and train a new one.

It’s gone on for a while

You always have good and bad days at a startup. You win a deal one day and lose one the next. You land a key hire one day, and someone quits the next.

An abyss is more persistent. It’s when you go three months without adding a customer. It’s when you look at your team and wouldn’t mind if any of them quit. It’s when 25 investors in a row ghost you after you pitch them.

The right thing to do isn’t obvious

An abyss rarely has a straightforward path of escape. If it did, it wouldn’t be an abyss. Let’s say your product is getting a lukewarm reception. You could convince yourself you’ll be OK once you add a few features. Or maybe you need to target different customers. Maybe you just need to give it more time. Or maybe you should shut your startup down and move to Bali.

When the right thing to do isn’t clear, you’ll likely be slow to act on it or suffer analysis/paralysis (or worse, paralysis without the analysis). You also might act impulsively and make fast but wrong decisions, sending you careening toward the next abyss. Doing nothing is dangerous, but doing the wrong something can be even worse.

You doubt yourself

Most founders hope their startup is the pinnacle of their career. Everything you’ve done up to now led to your having this idea, hiring this team, and building this product. You may have spent years dreaming about the day you could launch your own business.

You did, and now you are circling an abyss. You might feel like your life’s work is being soundly rejected, which leads to crushing self-doubt. You wallow in existential angst at the exact moment you need to think clearly, focus, and take decisive action.

At this point, you might wonder, “Alright, Nietzche, now I feel even worse. What do I do now?” There is no guarantee your abyss can be evaded, but you can try a few things:

Don’t panic when you approach the abyss

You have to be an optimist to start a startup, believing that your idea and your team are so great that you’ll be an exception to the rule that most startups fail. You have to believe your product will resonate, your team will get along, your revenue will grow, and the abysses will bypass you and haunt some lesser founder.

But a founder who expects everything to work out can be less resilient when they look up one day and see an abyss looming. Stay confident, yes, but don’t be shocked when the abyss looms. Face reality and get to work escaping that abyss once you are on its event horizon. Many other founders have.

But like most advice, don’t go too far in the other direction. If you expect to see an abyss around every corner, you can become hyper-vigilant, look for problems, and react too quickly at the first sign of trouble. Every problem isn’t going to kill your startup but stay attuned to the ones that might.

Plot your escape trajectory early

Founders have the most to lose and the most to gain from their startup, much more than their team and investors. You’d think they’d be the most sensitive to problems at their startup and be the quickest to react. They often aren’t. They sometimes see them even later than their team does.

For example, if your first three customers tell you they are switching to a competitor, you can try to convince yourself that you’ve just hit some bad luck. Maybe the customers just lack vision. Maybe you can add one killer feature to get them back. And you may be right. You certainly don’t want to overreact and toss out your plan or bail on your entire startup. Most startups take time to build momentum.

But don’t fall victim to wishful thinking. Take the problem seriously and start working on it. Talk to those customers. Gather data. Start building options and weighing them. You don’t want to make a rash decision based on fear, but the earlier you act, the more time you’ll have to make good decisions based on a clear-eyed assessment of the situation.

Let nothing cloud your judgment

As a startup founder, you should educate yourself on mental models and conceptual biases2. They come in handy all of the time, especially when hard decisions loom, and the emotional side of your brain is battling the analytical side.

For example, the Sunken Cost Fallacy3 often trips up founders. They have often spent years working on their ideas, and when they start to get poor customer feedback, they have a strong bias to ignore or downplay it rather than accept that they may need to pivot and “lose” some of the investments they have made. Sunken costs are behind many people problems, like being unwilling to accept that you spent a year hiring and training a VP of Marketing who isn’t working out since you’d have to devote a second year to hiring and training a replacement, “losing” the work you put into the first one.

Another is the Ostrich Effect4, which is the tendency to avoid bad news so that you don’t have to deal with the consequences. The Ostrich effect is why a founder can ignore an abyss gazing right at them when everyone else can see it clearly.

We can keep going, but these are all different versions of the same thing: you have to be ruthlessly honest with yourself about your startup, no matter how hard it is. Your team relies on you to face reality; it’s your job description. The best founders are almost eerily good at this. They can dispassionately focus on the right thing to do right now while being unsentimental about tossing out everything that came before.

See abysses as opportunities

It’s annoying to be told, “Every problem is an opportunity,” especially by people sitting on the sidelines and not chewing glass. But there is truth to it. Besides, you don’t have much choice.

Most successful startups veered close to an abyss at some point, and many emerged stronger. Sometimes, like at Slack, the abyss was the realization that the first product wasn’t working and the startup needed to pivot to an entirely new idea5. Sometimes, the abyss was slow product adoption, and the company responded by refining its go-to-market. Many startups have turned over their management teams multiple times.

Your abyss is telling you something. Ask what it is and if you can use it to make your startup stronger. In the worst case, you might learn that you don’t have a path to success, but you should be grateful to know that now instead of spending more years of your life working on something that won’t go anywhere.

Bring in your team

When that sense of dread that you’re at an abyss looms, it’s tempting to downplay it with your team. Managing your own psychology is hard enough without adding the burden of calming down a dozen of your teammates. And yes, you don’t want to share every negative thought with your team. They don’t need to join you on every plunge of your emotional rollercoaster.

But an abyss isn’t just a bad day. It’s an existential threat to your startup. By the time you’re sucked into it, your team sees it too. They’ll be more nervous if they don’t hear you talk about it than if you do. No one wants to work for a deluded boss.

Bring them in early. Get their help diagnosing the problem so you can be precise about what problem you are trying to solve. Solicit possible solutions from them and enlist them to implement them.

If you have a board, investors, or external advisors, this is also an excellent opportunity to put them to work and let them prove their “value add.” If they are worth having in the first place, they’ve seen many abysses in their career, and they will have stories of how they’ve worked with other founders to solve them. Some founders worry this will cause investors to lose the faith, but it might have the opposite effect of solidifying their commitment to you since they can take some credit for helping you leave the abyss behind.

To put the abyss into your rearview mirror, you’ll have to hunker down and get things done, which we’ll cover next in Embrace the Grind.

If you have feedback or suggestions for future posts, please comment or contact us at michael@nextfounder.co.

Many thanks to my friend Ricky Yean for the idea for this post. This piece by Ben Kuhn also covers some great abyss-staring stories.

The Wikipedia list of cognitive biases is an excellent place to build up your radar for your biases. The classic Charles Munger lecture on mental models is another great resource.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy occurs when people are reluctant to “lose” the investment they have already made in something even after they learn that the best decision going forward is to do something different.

The Ostrich Effect is when you try to avoid bad news so you don’t have to face the consequences. A common example is to avoid the doctor so you won’t have to face a diagnosis of a serious illness.

The Slack pivot from a gaming company to an enterprise software company is one of the best-known startup pivots, but it’s not uncommon. Many successful startups made course corrections along the way, although usually less dramatic than Slack’s.