Know Your X's and Y's

Or why so many startup management dilemmas come from the same place

The Next Founder helps founders build great startups. We offer advice on managing your mental health and productivity, hiring and managing great people, building a strong culture, and keeping people aligned and working on the right things. See the series overview at Welcome to The Next Founder and find out more about me at My Story.

"Given the opportunity, workers are eager to learn, grow, and take responsibility for their work."

— Douglas McGregor

“The only way you can make a man trustworthy is by trusting him, and the surest way to make him untrustworthy is to distrust him and show your distrust.”

— Henry L. Stinson

“The essence of the idea, radical at the time, was that employees' brainpower was the company's most important resource.”

— Peter Burrow, BusinessWeek (on the HP Way)

Sometimes they really are out to get you

You’ve learned to tolerate the mood swings that go with being the technical co-founder of a fast-growing 40-person startup, but you’ve never dreaded coming to work until now. It started three weeks ago when you added Chad, your new VP of Sales, to the team.

When Chad started, you tried to build rapport with him and oriented him on your product team and processes. But things went south at last week’s leadership team meeting when you announced that your team slipped a product deadline by two weeks. Chad has been standoffish and surly ever since.

Your co-founder senses the tension, too, so she organizes a team dinner on Friday, hoping that taking the leadership team offsite to get to know each other would ease the tension. Unfortunately, the dinner only made it worse.

After sangria and tapas raise his blood alcohol and blood sugar levels, Chad comes to life and starts a rant about how “things need to change.” He says he “holds his team accountable,” but other teams at the company “escape the consequences.” He beats his chest about whipping his team into shape, whereas other managers (clearly you) let your people “do as they please.” He proposes that your team would miss fewer deadlines if you docked their pay when dates slip. He questions your startup’s work ethic since he sent some emails last night at 8 pm that no one answered until the morning.

Chad seems utterly unimpressed by your startup, and the rest of the dinner is awkward. You are in for some painful discussions next week, but they’ll be easier if you Know Your X’s and Y’s.

What are we actually arguing about?

You’ll be tempted to charge into Chad’s office on Monday and tell him why he’s wrong, defending how hard your team works and their track record of delivering a great product. He’ll say that he joined your startup to raise the bar and that you need to step up your game and drive people harder. You’ll have different versions of this debate every few weeks unless you pinpoint the core of your disagreement.

The core of your disagreement might be different mental models for what motivates people and how to manage them. His model is more “Theory X,” and yours is closer to “Theory Y.”

Theory X and Y is a framework popularized by Douglas McGregor at the Sloan School of Management in the 1950s1. If you haven’t heard of Theory X and Y, that’s because it was so successful that it’s baked into modern management and is rarely mentioned explicitly. But like so many golden oldies, each generation seems doomed to rediscover it, which is what you and Chad are doing.

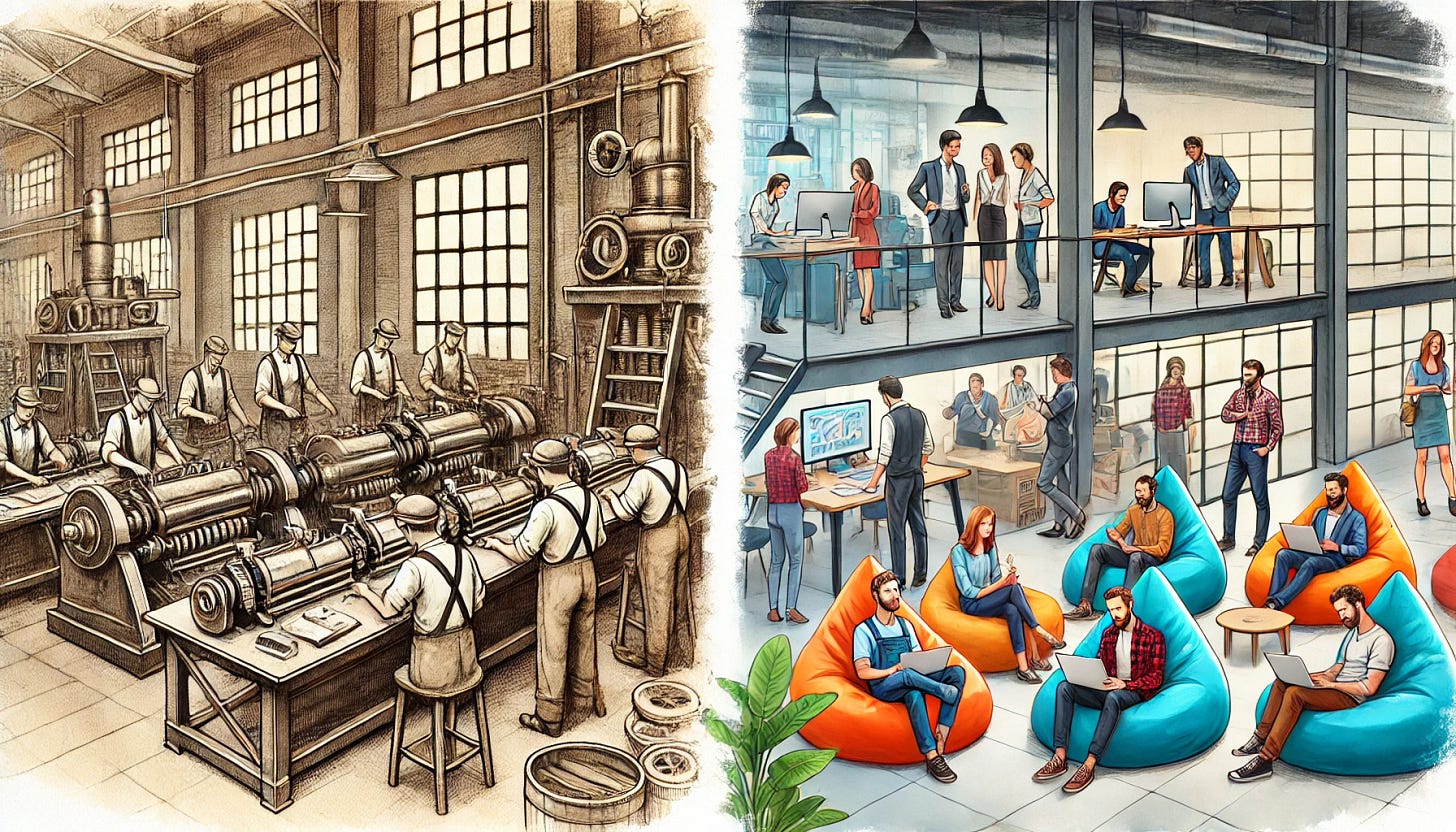

Theory X is grounded in the Industrial Revolution, where many workers worked in manufacturing jobs. Their jobs had limited scope, and their output was driven by how many hours they worked. Management’s job was to decide what the workers should do and how to do it, then push them to do it for as long and hard as possible.

Theory Y is grounded in the knowledge economy, where the work requires a high level of skill and creativity, and workers are valued more for what they know how to do than how many hours they do it. They are trusted to work more autonomously alongside management and contribute their own ideas.

Theory X and Theory Y help answer questions like:

Are employees labor or capital?

Theory X says employees are hired to execute tasks and are interchangeable and easy to replace. Theory Y says employees are “the talent,” possessing rare and valuable skills, where the value of a company is a sum of the skills of its team, in the way that the value of a pro sports franchise comes from its star players.

Are employees motivated by incentives or by the work?

Theory X suggests people are motivated by keeping their jobs and preserving their paychecks. Theory Y says they are motivated by doing great work, building their skills, contributing to a mission, and supporting their teammates. Many of the ideas behind Theory Y were motivated by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, developed around the same time.2

Do managers have to compel employees to work?

Theory X assumes that employees are lazy and will try to get away with doing as little work as possible when management isn’t looking. Theory Y says most workers can be trusted and are internally motivated to deliver good work because they want to contribute to the mission, grow their skills, and support their teammates.

Is management a partner or an adversary?

Theory X employees and their management clash over money, hours, and working conditions in a zero-sum game, with labor unions often mediating. Theory Y sees management as another role on the team that partners with the people who work for them. It’s not uncommon for Theory Y employees to outearn their managers, just as pro sports stars are often paid more than the coach.

Do you pay people for their time or their skill?

Theory X suggests that the more hours a person works, the more they deliver, and management’s job is to extract as many hours from them as possible. Theory Y says employees add value to their company by deploying their creativity and talent, in the way Nicole Kidman adds value to a Netflix Series by being Nicole Kidman, not by acting for more hours.

Does the management team assign tasks or assign problems?

A Theory X manager sees their role as deciding what work needs to be done, breaking the work into tasks to assign to individual workers, and supervising the tasks. Theory Y managers trust their teams not just to execute tasks but also to help decide which tasks need executing in the first place.

Is the workplace a hierarchy or a network?

Theory X takes a more hierarchical view of a corporation, where management possesses the information their team needs to know and then carefully transmits it down the org chart. A Theory Y corporation is more of a network where employees communicate with anyone they need to across the company to get work done, regardless of their department or level.

Theory Y and the tech industry

The tech industry probably embraces Theory Y more than any other industry. A tech firm creates new, unique, differentiated products requiring skill and creativity to invent. Hewlett Packard, arguably the prototype of the modern startup, pioneered many Theory Y-based management practices with the “HP Way” in the mid-twentieth century.”3 These have become standard in the tech industry.

You could argue that Theory Y peaked in the early 2000s when companies like Google and Facebook hired as many talented people as possible, showered them with benefits like free food and dry cleaning, and gave them leeway to work on problems they found interesting, including Google’s “20 percent time.”4 The most hilarious scenes from the HBO Series “Silicon Valley” mocked Theory Y taken to excess, portraying the employees of a Google-like company spending their days enjoying free sushi and sunning on the roof while their employer looked the other way since it would be worse if they left for a competitor.

Of course, the story is more complex. As with any binary framework, the answers lie in the middle. Yes, employees are motivated by more than money, but compensation is a significant driver of why they work for you. Yes, you hire people for their skills and creativity, but they do deliver more if they work more hours, up to a point. Yes, you should empower your team, but sometimes you have to overrule and make hard decisions. Yes, everyone says they want to build a Theory Y culture, but when times get hard, Theory X creeps in, sometimes out of necessity.

But building a successful startup means knowing what mix of Theory X and Y to apply to which situation, starting with:

Get leadership aligned

Some startups underperform because their leaders hold different ideas about what kind of people to hire, how to manage them, and what culture to build. A fundamental mismatch can even cause a co-founder breakup, often discovered only when the founders start to grow the team and hit these management dilemmas.

Talk to your co-founders about the kinds of people you want to hire and how much autonomy to give them. Discuss which decisions you want to drive vs. which ones you want to trust the team with. Pick a few hypothetical management dilemmas and ask how you’d approach them.

When interviewing potential leaders like Chad, ask questions that reveal their management philosophy and ensure it aligns with the culture you want to build. Don’t expect to agree completely. For example, Heads of Sales like Chad often employ some Theory X tactics since managing a quota-driven Sales team differs from managing an Engineering team. But you still want to uncover if you have different core assumptions about what motivates the kind of people you want to hire.

Hire for Theory Y

Most management challenges have less to do with how you manage your team and more to do with what team you hire in the first place. You can only build a Theory Y culture if you have people who can handle it. Start by looking for signs of Theory X and Y thinking when you recruit:

You generally aren’t looking for candidates who just need a job and will take the first offer they get. And you don’t usually want a candidate who will simply join whichever company pays them the most. Instead, look for signs that a candidate is specifically drawn to building a startup at your stage, wants to work on products like yours, and understands what that will take. They should ask many questions about your business and culture, and you should see them noodle over whether it’s a good fit for what they want, especially for more senior candidates.

Get a sense of how a candidate expects to work with others. Ask for stories about conflict or cooperation with co-workers and management from previous roles. Look for evidence that they envisioned their role as strengthening their team instead of acting as a free agent. Even if they were unlucky enough to have a lousy manager or unreasonable co-workers, ask how they tried to improve the situation. When you find a candidate who tells you that everyone at their last company was an idiot, proceed with caution. And always check references and push on the same topics.

And even though you want people motivated by more than a paycheck, never use their enthusiasm for your startup against them to justify underpaying them. And, of course, if you want people to act like owners, you need to make them owners. Give them generous stock option grants and regularly remind them that their job is to find ways to make that stock worth something.

Hold people to high Y standards

Given the choice, most people would rather work for a Theory Y company. We all want to be empowered, trusted, and given latitude to do our best work. But it’s a common misperception that Theory Y jobs are easy. Notwithstanding our friends on the roof in “Silicon Valley,” a Theory Y job can be brutally hard.

Theory Y means high expectations for people to live up to the trust they are extended. They have to deliver great work without being micromanaged. They have to generate creative ideas and anticipate problems. They can’t wait to be told what to do but should come to you with ideas. They should understand your mission and strategy and find ways to make them happen.

When you recruit people, confirm they understand these expectations and can live up to them. If they don’t, they either need to improve quickly, or you have to let them go.

Give people problems, not tasks

Many startup leaders claim they empower their team, but too many define empowerment as “I trust you as long as you do exactly what I would have done.” This isn’t empowerment; it’s dressed-up Theory X.

Don’t fall into the trap of “leadership does the thinking, and the employees implement the leaders’ ideas.” You want every team member to contribute ideas, down to the new graduate you hired yesterday. You don’t hire people because you are too busy to do the work yourself. You hire them because they are better at the work than you are.

For example, many of the best-run software companies build “product teams,”5 where a cross-functional team of engineers, designers, and product managers team up to solve a set of problems tied to a user persona or business problem. The teams become experts in their product area, understand their users’ problems, and propose and build solutions to solve them. Management doesn’t tell them what to do. Management expects them to figure out what to do.

Examine your attitude towards your team. Do you assume you know more about every aspect of their work? If you do, does that mean you have the wrong team? Do you believe good ideas can come from anyone? Do your people know you expect them to bring those ideas?

Always ask if you are giving your team problems to solve and space to solve them. You can still give feedback and overrule when needed, but make that the exception, not the baseline, and when it happens, ask why.

Build a see-through startup

An unfortunate leadership antipattern is when leaders hold onto crucial information and dole it to their subordinates on a need-to-know basis. These info-hoarding managers often use excuses like “We don’t want to distract people” or “They can’t handle it.” This is seldom the case.

Those managers employ Theory X thinking, believing their title gives them a unique ability to manage complexity and risk that their mortal subordinates could never dream of. Managers are as susceptible to Imposter Syndrome as anyone else. Holding on to information can become a way for them to justify their position and give them the right to lead.

You should rarely tell a team member, “If you knew what I knew, you’d understand why we have to do this.” Why wouldn’t they know what you know? Why didn’t you tell them?

Build a transparent culture where the whole team can access the same information you can. Communicate your strategy and goals aggressively. Share your vision. Share all of your forecasts, customer meeting notes, and product plans. Make your file shares and Slack groups public. Have a company meeting where anyone can share important news and insights.

You can’t get your team’s best thinking without giving them the whole picture. Once you do, great things will happen, more will get done, and your life will get easier since you won’t need to stay on top of every person and project. Theory X management is no fun.

Don’t regress to Theory X as you grow

All founders want to grow their startups, and the faster you grow, the more critical Theory Y becomes. As you add people, projects, and complexity, your only hope of executing well is to harness your team’s collective brainpower, let them make decisions, and let them act without asking permission.

Unfortunately, the exact opposite happens at many startups. As they grow, they reduce their trust in the team, add more approvals and roadblocks to getting things done, and share less information. They regress to Theory X just when they need Theory Y the most.

Sometimes, the startup’s culture goes bad after it hires managers from larger companies and they bring their BigCo culture along with them. They build silos. They carefully control communication. They add multiple layers of approval for decisions. Founders often go along with this, assuming that maybe this is what scaling looks like.

Sometimes a startup becomes more risk-averse as it grows, and it starts to focus on preventing bad things from happening instead of encouraging good things to happen. A single employee abuses the expense report policy, but instead of simply firing or disciplining that employee, the company adds layers of approvals to expense reports that signal to the employees that none of them are trusted. Saving a few thousand dollars comes at the cost of demoralizing a team capable of generating hundreds of millions or billions of dollars in market cap.

Many people who have worked for growing startups can tell stories about the day their startup “jumped the shark”6 and regressed from a great place to work into an ordinary and mediocre corporation where the team is no longer trusted and is kept in the dark. The employees leave and watch from the sidelines as the startup’s Glassdoor scores plummet and results decline.

Yes, you need to add experienced managers as your startup grows. Yes, you need a few more processes and controls. But none of them help you if they come at the cost of your best people feeling like you are treating them like children.

We will cover these topics more in-depth in future chapters.

The Wikipedia Article on Theory X and Theory Y is a good overview of how modern management evolved throughout the 20th Century.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs addresses human needs and motivations, from the most basic (food, water, and shelter) to the most transcendent (love, learning, and impact). If you’ve ever used the term “self-actualization,” you can thank Maslow.

I’m old enough to remember when Silicon Valley startups modeled themselves after the OG startup, Hewlett Packard.

Although it’s unclear how real Google’s 20 percent time ever was, it’s undoubtedly true that many tech companies give their people more freedom to pursue interesting ideas than other industries.

Silicon Valley Product Group has some of the best books and essays on empowered product teams and other topics on building technology products. It’s a must-read for startups.

”Jumping the Shark” is the moment when a previously awesome thing suddenly becomes lame. It comes from an episode of the 70s sitcom “Happy Days” with a ridiculous post-Jaws plot involving a main character, Fonzie, jumping a shark with his motorcycle. An entire nation agreed the next day that Happy Days was no longer worth watching. A modern-day equivalent might be the “Bring a Zombie to King’s Landing” episode of Game of Thrones.